| Updated March 19, 2024

Architects and owners are realizing, even in arid climates like Utah, that outside applications of stainless guardrails often need careful review. Why, because stainless steel, despite common misconception, is subject to corrosion and will turn brown.

One of the main culprits is ice melt.

Walkways, stairs and ramps with stainless railing are usually treated with ice melt to keep snow and ice from forming on the concrete.

Ice melt has a chemical composition, combined with water, that will attack the stainless railing and cause it to corrode and turn brown. Owners that pay high dollars for the Stainless look are not happy when their expensive railing starts to fail.

The answer is specifying t which has corrosion resistance because of an added composition Molybdenum (more than you want to know). Molybdenum is added to the stainless steel make-up to help resist corrosion to chlorides, sodium brines and phosphoric acids.

There are a couple of “gotcha” points, however, that owners, architects and GC’s should know.

Type 316 Stainless and Type 304 Stainless are virtually identical in visual appearance. Only Metallurgists with the right testing equipment can tell between the two.

Because of the similar appearance, it is easy for sub-contractors to, whether on purpose or accident, fabricate and supply the wrong type of stainless steel.

To make matters trickier, it usually takes a couple of years to spot the problem. The stainless steel will slowly begin to appear as if it were rusting, turning dark brown and dingy.

With all of this in mind, it is important for the General Contractor and Architect/Owners to get certified paperwork to document that the project, if called out as Type 316 Stainless, was actually supplied to that specification.

Paperwork should verify the type, date and quantity purchased for the job.

Another gotcha is verifying that the welding filler rod used to weld the Type 316 Stainless was correct. Far too many sub-contractors use the wrong filler materials which are just as important as the raw components being welded together.

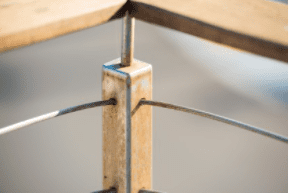

Ultimately, the filler materials are just as susceptible to corrosion as the main body of the railing. We see stainless steel railing with “ring-around-the-collar”, as it were, from a fabricator that used the right materials for the body of the railing but the wrong filler material for the seams.

Stainless Steel—no matter which type—can be, and often is, contaminated by carbon steel. Contamination happens when carbon steel particles lodge themselves into the stainless.

Traditional fabrication shops work with both materials. Grinding pads, for example, that are used on steel and then re-used on stainless steel leave a carbon residue that transfers from the steel to the stainless steel.

Steel tables do the same thing. When a piece of stainless steel tube is manufactured, laid, maneuvered, clamped or slid across a steel table, the carbon from the steel table embeds into the stainless tube.

Even steel forklift tines will embed carbon particles into the stainless steel.

What happens is that the embedded steel particles will rust and bleed on the outside of the stainless steel. It looks like the stainless is failing but the reality is it is simply exposing the contamination that happened when the carbon found it’s way, haphazardly, onto and into the stainless.

This is often combated by passivating the stainless steel and/or making sure the equipment and fabrication processes are all done to avoid contamination, like welding or assembly the guardrail on wood tables instead of steel tables.

Low bid mentality can create situations where sub-contractors cut corners to win bids—that is nothing new to report. Using reputable sub-contractors is important but even reputable firms can make mistakes or have weak links inside their organizations.

In summary, some of the key elements to making sure a project’s stainless steel is bid and fabricated correctly is as follows:

It pays to have validation methods in place when the owner is taking enough concern to specify Type 316 Stainless Steel. That specification is usually there for a reason.

Type 316 Stainless is usually 30-40% more expensive than traditional Type 304 Stainless Steel. If GC’s have a grouping of subs at one price point and one or two quite a bit lower, they may well suspect that the materials quoted were the wrong type of stainless. It is shockingly easy to miss in the specifications.

Ultimately, the goal is to create long-lasting, beautiful railing that will stay that way for a long time.

We would love to assist you with any of your stainless steel or ornamental metal needs.